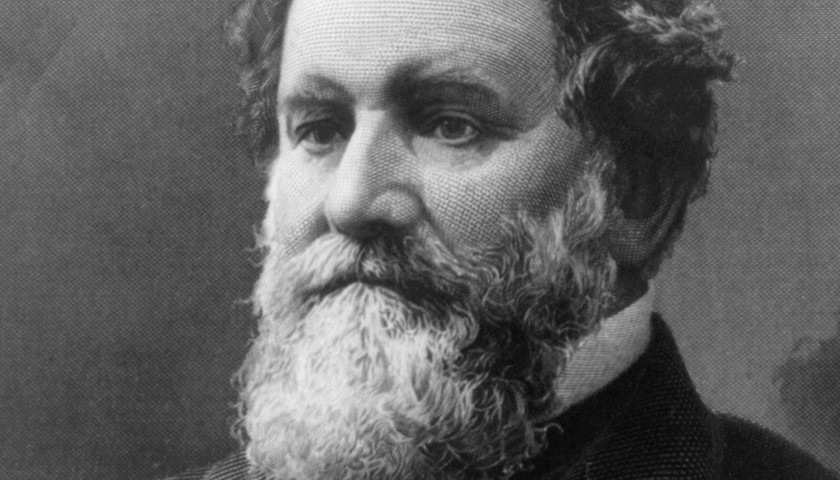

Cyrus Hall McCormick was born in 1809 on his father’s rural farm tucked between the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains in an America that was still developing “beyond the struggle for food.”

His father, Robert, owned four farms totaling 1,800 acres as well as two grist mills, two sawmills, a smelting furnace, a distillery, and a blacksmith shop. Robert invented new types of machinery in his spare time, such as a hemp-brake, a threshing machine, and a bellows, and worked with his sons on new inventions in a log workshop on their Virginia farm.

Robert made two failed attempts at building a reaper, the agricultural wonder his son would later become famous for perfecting.

“Cyrus McCormick was predestined, we may legitimately say, by the conditions of his birth to accomplish his great work. From his father he had a specific training as an inventor; from his mother he had executive ability and ambition; from his Scotch-Irish ancestry he had the dogged tenacity that defied defeat; and from the wheat-field that environed his home came the call for the reaper, to lighten the heavy drudgery of the harvest,” writes Herbert N. Casson in his 1909 biography of McCormick.

At the time of McCormick’s birth, the 30-year-old country was marked by a “desperate struggle to survive” and a “chronic quantity of misery.” There was an urgent need for better methods of farming.

Twenty million acres of American farmland were sold between 1810 and 1820, and nine out of every ten Americans worked on a farm. But they used wooden plows, sickles, and scythes—the tools of “failure and slavery and famine,” as Casson describes them.

McCormick began laboring on his father’s farm at the age of 15, but quickly discovered the severity of swinging a “cradle against a field of grain under a hot summer sun.” At first, he developed a smaller cradle that was easier to swing, but this still wasn’t enough.

So he started where his father left off and by the summer of 1831 had completed the world’s first mechanical reaper, built in the same log shed he worked in as a child. His mechanical reaper had six key features: a divider, which separated the grain that was cut from the grain left standing, a reciprocating blade, a row of “fingers” that supported the grain while it was cut, a revolving “reel” to straighten the grain that had fallen, a platform to catch the cut grain as it fell, and a wheel to carry the weight of the machine and operate the blades.

The reaper was pulled through the fields by horses and automatically cut, threshed, and bundled grain. According to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), McCormick had singlehandedly increased a farm’s potential yield at least tenfold, but farmers remained uninterested in the new invention for at least the first nine years of its production. Cannon suggests this hostility was partially due to the fact that farmers were concerned about being replaced by a machine.

“These men were hardened and bent and calloused by the drudgery of harvesting,” Cannon writes. But McCormick was determined to improve his invention and by 1834 he secured his first patent. He also utilized a number of “novel business practices,” MIT suggests, and pioneered the idea of offering lenient credit to purchasers.

In addition, McCormick’s reaper had a written performance guarantee of “15 acres a day,” and he provided readily available replacement parts.

By 1841, McCormick had successfully educated the farming population on the benefits of his new technology and moved his operation to a factory in Chicago by 1847 to begin mass production of the reaper.

His invention allowed the Midwest to become the breadbasket of the nation and freed up countless workers to work in the factories during the industrial revolution. McCormick received the Gold Medal at the London Crystal Palace Exposition in 1851 and was elected to the French Academy of Science for “having done more for agriculture than any other living man.”

Jo Anderson

It’s difficult to trace a slave’s contributions to an invention, but there’s evidence to suggest that McCormick was assisted by Jo Anderson, a slave on the McCormick family farm. Anderson had “as much to do with the later development of the reaper as Cyrus McCormick,” said Lester R. Godwin, a retired curator of the McCormick farm, in a 2013 article for the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

McCormick’s grandson, also named Cyrus McCormick, gave Anderson the credit he was due in his 1931 book The Century of the Reaper.

“Jo Anderson was there, the Negro slave who, through the crowded hours of recent weeks, had helped build the reaper,” he states in the book. “Jo Anderson deserves honor as the man who worked beside him in the building of the reaper. Jo Anderson was a slave, a general farm laborer and a friend … and the Negro toiled with him up to the hour of the test and after.”

Some historians suggest that the two men were more like brothers and friends than anything else. They were born just one year apart from each other and likely grew up working on the farm together. Anderson’s own writings show that he was freed by McCormick before the Civil War, but he couldn’t live as a free man in Virginia. So McCormick hired him out to friends and returned a portion of the earnings to Anderson.

Other family records obtained by the Richmond Times-Dispatch indicate that McCormick purchased a log cabin and a small plot of land for Anderson and supported him up until his death.

– – –

Anthony Gockowski is managing editor of Battleground State News, The Ohio Star, and The Minnesota Sun. Follow Anthony on Twitter. Email tips to [email protected].